Confidence builder

Northeast Asia should draw on ASEAN's successful experience in forging regional cooperation

The 11th China-Japan-Republic of Korea Trilateral Foreign Ministers' Meeting held in Tokyo on March 22 was another important diplomatic event in Northeast Asia following the trilateral summit held in May last year, which convened after a four-and-a-half-year hiatus. The top diplomats of the three countries reached consensus on advancing practical cooperation in "six key areas" in a comprehensive and balanced manner, and laid the groundwork for the upcoming 10th China-Japan-ROK Trilateral Summit Meeting.

However, whenever progress is made in the cooperation among the three neighbors, pessimistic voices about regional cooperation will surface. Some argue that the three countries lack shared values and their cooperation is, at best, a marriage of convenience formed in response to the uncertainties created by Donald Trump's second term as US president. Some go so far as to say that Northeast Asia is inherently an anti-region — a region without the DNA for collaboration.

China-Japan-ROK cooperation must first dismantle these misleading perceptions and build new standards and principles for regional collaboration based on objective, comprehensive and historical perspectives.

The roots of pessimism about China-Japan-ROK cooperation and Northeast Asian regionalism lie in using NATO and the European Union as benchmarks. Europe — particularly Western Europe — has long been regarded as the model of regional cooperation, with its dual engines of security (NATO) and economic integration (the EU) serving as the reference by which other regional collaboration is measured.

Northeast Asia lacks a collective defense mechanism such as NATO, and the Trilateral Cooperation Secretariat pales in comparison to the colossal EU headquarters in Brussels.

However, it is misleading to label Northeast Asian cooperation as "backward "based on the supposedly "advanced" model of European regionalism. East Asian cooperation emerged in the context of post-World War II decolonization and nation-building, which is fundamentally different from Europe's process of regional integration through centuries of warfare, including two world wars and the Cold War. Such simplistic comparisons are untenable.

Moreover, the Ukraine crisis has demonstrated that relying on regional military alliances to deter imagined enemies fails to deliver collective security — instead, it undermines the security of the region. Northeast Asia should not repeat this mistake by creating an East Asian version of NATO.

Northeast Asian cooperation has fared rather well when viewed through a historical lens. Japan and the ROK normalized their relations in 1965. China and Japan restored diplomatic ties in 1972. China and the ROK established formal relations in 1992. And the trilateral summit mechanism was launched in 2008.

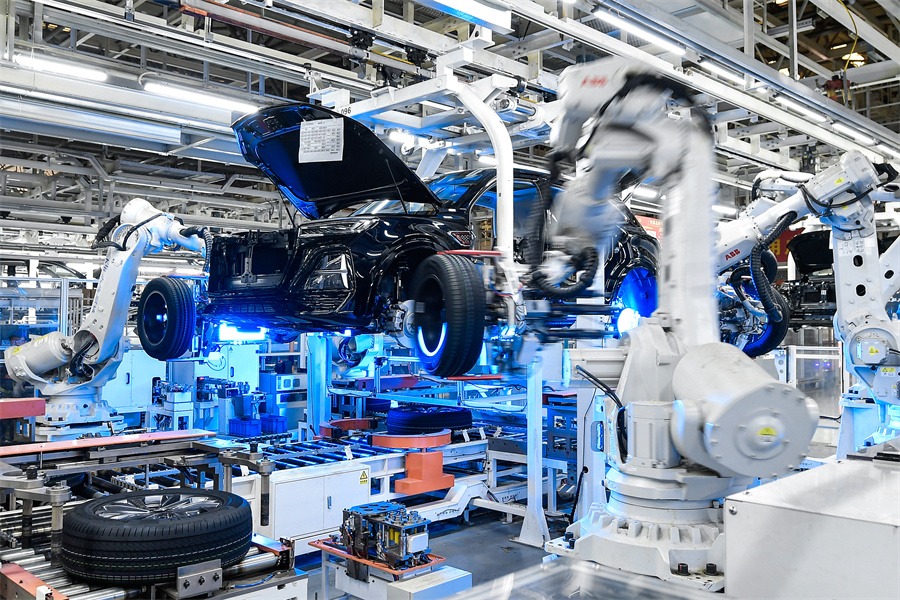

In 2014, a China-Japan-ROK trilateral investment agreement came into force, and in 2022, the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership took effect — effectively achieving a de facto trilateral free trade agreement by indirect means.

If European integration represents a form of de jure regionalism — a regionalism built on an extensive foundation of legal treaties and documents — then Northeast Asia exemplifies de facto regionalism.

The trade volume among China, Japan and the ROK has reached $800 billion, the three nations account for about 25 percent of global GDP, and their industrial and supply chains are deeply intertwined. How can anyone claim Northeast Asia has made no progress in regional integration? In reality, Northeast Asia has already become an interconnected economic and social community.

Northeast Asia should draw on the Association of Southeast Asian Nations' successful experience in forging shared regional values amid diversity, rather than uncritically adopting the Western model based on so-called universal values.

Intertwined interests alone are insufficient to build a cohesive region. Instead, it requires the cultivation of identities, values and norms shared by regional members. Washington has sought to strengthen the US-Japan-ROK cooperation framework through two strands: common security threats and so-called democratic values.

And both Japan and the ROK have invoked "shared values" to mend bilateral ties. But when relations soured, Japan removed the phrase stating that Japan and the ROK are neighbors that "share fundamental values" from its Diplomatic Bluebook, which raised the question: how could the universal values vanish overnight due to political frictions?

Some believe it is unrealistic, if not naive, to build regionalism in Northeast Asia because the region is plagued by formidable security challenges, territorial disputes and historical issues. However, the shared values in the region can be built upon real and well-intended interactions among neighbors.

Southeast Asia was once viewed as the "Balkans of Asia" after World War II, and when ASEAN was first established, it was widely predicted to be a failed attempt at regional integration because member states had vastly different political systems, levels of economic development, religious and cultural backgrounds and territorial disputes left over from former colonial rulers.

Despite all the odds, ASEAN has maintained peace among its member states since its establishment in 1967, and has proved to be the most successful regional bloc in the developing world. The success of ASEAN can be attributed to the fact that regional countries have forged shared values that suit the needs of the region. The stability of ASEAN stems from the political and social stability and economic growth of member states; and relations among regional countries are based on genuine multilateralism that is non-discriminatory and inclusive.

The essence of the "ASEAN Way" is to cultivate shared values among regional countries.

For Southeast Asian nations, the top priority is to address domestic challenges — economic development, improving people's livelihoods and achieving ethnic unity — none of which could be solved through military means. If they get dragged into bloc confrontations between external powers, their precious resources would be wasted.

To preserve regional stability, ASEAN has further expanded multilateral cooperation frameworks with other major countries with ASEAN at the core, such as the ASEAN Regional Forum, the "ASEAN+3" and the East Asia Summit.

The key to overcoming pessimism about Northeast Asian cooperation is to build confidence. First, regional countries should not compare Northeast Asian regionalism with the models of other regions. Second, they should cultivate shared values and improve mutual recognition.

Neither overestimating its achievements nor underestimating its resilience, Northeast Asia can chart a viable path forward — forging a distinctive regionalism through positive interactions among neighboring countries.

The author is a professor at the School of International Studies at Nanjing University. The author contributed this article to China Watch, a think tank powered by China Daily.

Contact the editor at editor@chinawatch.cn.