Horns of a dilemma

Japan is seeking strategic and mutually beneficial relations with China while still retaining the perception that its neighbor is the greatest strategic challenge

On Feb 7, Japanese Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba made his first visit to the United States after taking office. The joint statement issued after his meeting with US President Donald Trump criticized China on issues related to the Taiwan Strait, the East China Sea and the South China Sea, and stated that the deterrent and response capabilities of the US-Japan alliance would be strengthened.

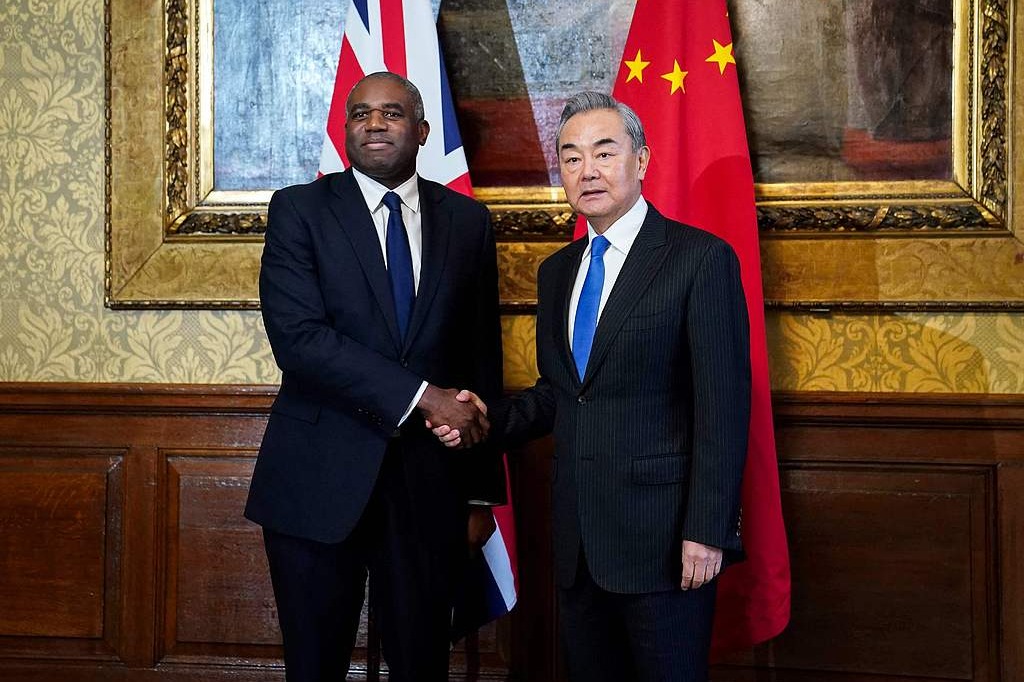

Before this, Ishiba had repeated his desire for improved Sino-Japanese ties and expressed his hope of visiting China as soon as possible. Last November, Chinese President Xi Jinping met with Ishiba during the APEC summit in Lima, Peru, reaffirming the political consensus on building a strategic, mutually beneficial relationship. Also that month, Takeo Akiba, the Japanese national security adviser, visited China and had high-level political talks with Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi. Japanese Foreign Minister Takeshi Iwaya visited China in the subsequent month. This was the first official visit to China by a Japanese foreign minister since the start of April 2023.

From China's perspective, Japan appears to be making active efforts to improve bilateral relations on the one hand, while on the other, it is vigorously sensationalizing negative perceptions of China, creating a contradictory and duplicitous stance. This duality and contradiction are most evident in Japan's Diplomatic Bluebook 2024. The report mentioned that Japan will promote a "mutually beneficial relationship based on common strategic interests" with China for the first time in five years. However, the Bluebook retains the previous edition's perception of China, positioning China as the greatest strategic challenge Japan has ever faced. During his state visit to the US, former Japanese prime minister Fumio Kishida linked a major shift in Japan's defense policy to China being regarded as Japan's greatest strategic challenge in his speech to the US Congress. This raises questions about the direction of Japan's China policy and whether the improvement in Sino-Japanese relations will merely be a brief Indian summer or lead to sustainable progress. It is believed that the essence of the duality and contradiction in Japan's China policy lies in the context of great changes in international relations, where Japan is at a critical juncture of seeking direction, reflecting a drift in its strategic cognition.

The strategic agenda of a nation largely depends on its "strategic cognition", and the core of this cognition lies in observing and analyzing the fundamental perception framework of international relations. After Japan was defeated in World War II, its perception framework of international relations was fundamentally shaped by the US-Japan alliance. Aligning with the US, the world's most powerful nation, and integrating itself into the US-led international order became the cornerstone of Japanese foreign policy. In the early post-Cold War era, Japan briefly entertained discussions about moving toward a multilateral strategic direction, but these discussions quickly faded. At the beginning of this century, the strong tendency of the US unilateralism displayed in its war on terror further reinforced Japan's perception of the world moving toward a unipolar order. Some scholars even argued that the world was under the rule of the American empire.

This perception began to shift after the 2008 financial crisis. Statements by then-US president Barack Obama, who took office in 2009, such as "the US would no longer act as a world policeman", were often cited by Japan as evidence of the end of the unipolar world and the decline of US global leadership. During Donald Trump's first term, his "America First" policy and the uncertainties he showed in dealing with alliances and free trade further solidified Japan's perception of these changes. In 2021, with the Joe Biden administration in power, the hasty US withdrawal from Afghanistan, the lack of global support for the severe economic sanctions against Russia following the Ukraine crisis, and the Israel-Hamas conflict, indicated a decline in US influence in the Middle East, and Japan has come to view international relations as undergoing a fundamental transformation. Recent Japanese diplomatic documents frequently mention that international relations are at a historic turning point and emphasize the importance of the Global South, indicating that it is at a critical juncture in shifting away from the long-dominant perception of a US-centered unipolar world. Facing such a historic transformation, Japan is primarily engaged in a debate between two theories on strategic opportunity. A highlight of this major shift in strategic cognition is its relationship with China.

One theory holds that Japan fills the leadership vacuum left by the US in Asia. Proponents of this view believe that, although the US has identified China as its greatest competitor, domestic political divisions have weakened its willingness to intervene abroad; additionally, the US faces the immense strategic pressure of potentially having to engage simultaneously in Europe, the Middle East and Asia. Under these circumstances, Japan, based on its alliance with the US, is strengthening and consolidating minilateral security mechanisms such as the US-Japan-Republic of Korea, US-Japan-Philippines, and US-Japan-India-Australia partnerships. This approach aims to establish a maritime security architecture centered on a framework with Japan and the US as the dual axis in Asia. Such a structure would not only reduce Japan's sense of inequality vis-à-vis the US but also enhance its presence and leadership in regional affairs. This strategic logic requires the so-called China challenge or even "China threat" as a pretext to legitimize its actions. This is why we have seen Japan amplifying negative perceptions of China in recent years both domestically and internationally, which serves as an important contextual factor. The shortcoming of this mindset lies in Japan's need to allocate substantial resources to the military domain, raising questions about its sustainability for a country that has already been grappling with fiscal constraints. Nevertheless, taking a hard-line stance toward China can only backfire in Japan's efforts to expand its strategic space.

The other holds that Japan is integrating into a multipolar world. In this view, the US is no longer a democratic model, a leader in the free economy, or a reliable ally. The collective rise of the Global South means that the era of the US-led G7 dominating the international order is likely to come to an end, and the world is increasingly moving toward multipolarity. The biggest challenge facing Japan and developed European countries is the decline in their economic and technological competitiveness. Taking artificial intelligence as an example, DeepSeek signifies a weakening of the high-tech hegemony of the US. Moreover, it cannot be ruled out that other countries will develop new AI technologies in different ways. The multipolarity of technological innovation also represents a significant opportunity for Japanese companies to reorganize and reconstruct the high-tech industry chain. Taking former prime minister Kakuei Tanaka who proposed the plan for remodeling the Japanese archipelago as his mentor, Ishiba put forward the initiative of rebuilding the Japanese archipelago in the Reiwa Era that aims at regional revitalization and economic growth. Looking back, prime minister Tanaka's visit to China to normalize Sino-Japanese relations was crucial for Japan to maintain a stable international environment, especially in its neighborhood, and stabilizing its relations with China was a top priority at that time. Meanwhile, Japan cannot expand its space for external relations and economic cooperation or develop diplomacy with the Global South without having a good relationship with China, because China is deeply involved and plays an important role in many Global South frameworks.

Japan has reached a critical juncture of its strategic cognitive transformation. The competition between the two perceptions mentioned above will continue to fluctuate with changes in the domestic and international landscapes. China-Japan relations are facing both opportunities and challenges. It is like rowing upstream; failing to advance means falling back. The two sides should continue to strengthen communication at all levels, including strategic dialogue, and constantly seek to establish common ground in perceptions that fit the new era of China-Japan relations.

The author is a professor of the School of International Studies at Nanjing University. The author contributed this article to China Watch, a think tank powered by China Daily. The views do not necessarily reflect those of China Daily.

Contact the editor at editor@chinawatch.cn.